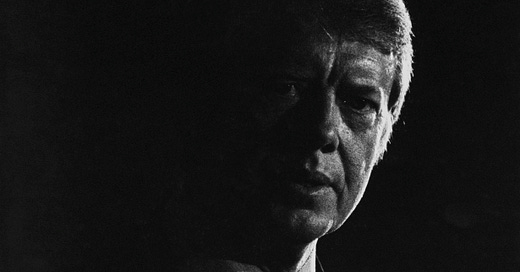

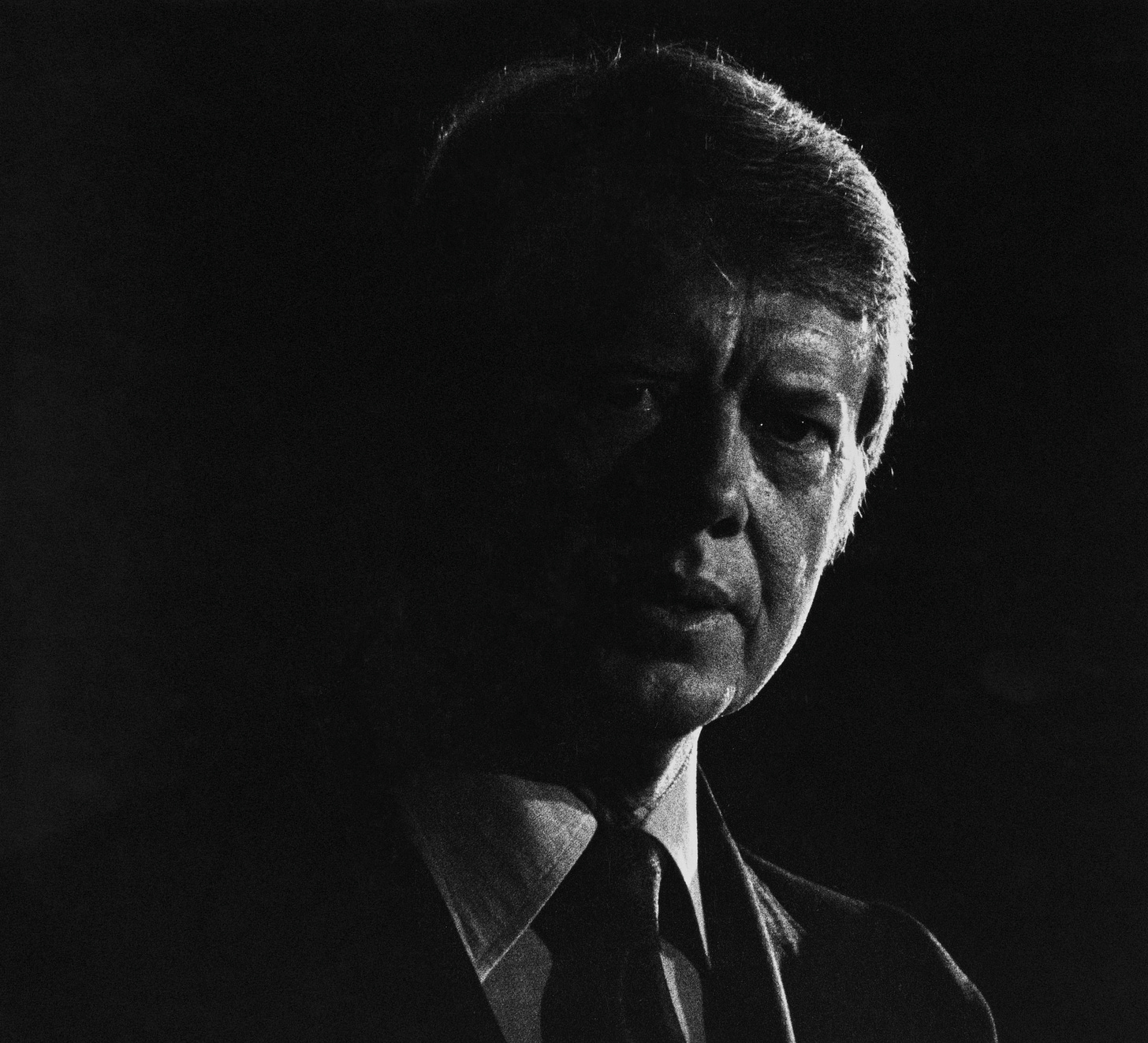

JIMMY CARTER’S MIXED LEGACY

As an ex-president he sought peace but in office he was an instinctive hawk

I’m a working-class kid from the South Side of Chicago, and I helped my mother survive in the 1950s after my chain-smoking immigrant father died of lung cancer. My father ran a laundry and cleaning store in the heart of the African-American neighborhood, and most of his clients had come to the big city in the north from the Deep South.

I learned a lot about Georgia in particular from a young employee named Sterling who pressed pants and suits in our shop and took me on more than a few Sundays to Negro league baseball games at Comiskey Park that took place every other Sunday when the White Sox played away games. I was too young to share the beers, which were used to top off swigs of whiskey, but old enough to get a sense of their enormous relief at getting out from the tyranny of Jim Crow in the Deep South.

Sterling was always telling me I would be OK, essentially because I was not afraid to work hard and, most importantly, I had white skin. There was no malice in the comment: it was just a fact of life. A few years went by, and my mother decided it was time to go live with my brother in California, and there was no need for me to keep running my father’s vaguely profitable business. She left, and I pisssed her off by immediately giving the keys to the store to the employees, including Sterling, and I moved on. I reminded them to pay the rent, and I fled to the University of Chicago, where I was attending classes when I could, and moved into a $12-a-week basement room, with a bathroom down the hall—a life of sheer bliss. This was in 1958.

I graduated from Chicago with a degree in History and English and, after not finding a good job, decided at the last minute to ğo to law school there. I did OK for a few quarters but burnt out. Then I bummed around for a year or so and did my mandatory Army service, and found my way by sheer luck into the newspaper business. By the fall of 1969, I had worked a decade as a wire service reporter for United Press International in South Dakota and then for the Associated Press in Chicago and Washington, where I spent a few years covering the Pentagon and the Vietnam War. I worked hard and did a lot of good stories—some of them implicating Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and his staff as liars. I also stalked the Pentagon cafeterias looking for junior officers back from the war at lunch and did all I could to get them to tell me about their tours. It was understood that what was said there stayed there.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Seymour Hersh to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.